| Jacopo Benci lives and works in Rome. His work encompasses photography, video & film, installation, performance, and has been shown in galleries and museums, and screened in festivals, in Italy, Argentina, France, Germany, Hungary, The Netherlands, Russia, Thailand, UK, USA. His most recent solo exhibition, Sentieri invisibili (Invisible paths) was held at Hybrida Contemporanea gallery, Rome, 2010. Since January 1998 he is the Assistant Director for Fine Arts at the British School at Rome. Marina Spunta - Let's start with your recent book entitled Jacopo Benci. Faraway and luminous, which was published in 2007 by the British School at Rome. This 400-page volume presents a comprehensive survey of your work between 1980 and 2007, in the fields of photography, painting, performance, video and film; it also includes some critical essays on your work. Most of the works published here had already been presented at various exhibitions and festivals in Italy and abroad. What choices did you have to make in selecting the material for this book? Jacopo Benci - The idea of this book began to take shape in 2000. Since 1993 my work started to develop in various media, i.e. photography, installation, theatre, performance, video and film. I noticed that the catalogue format, especially catalogues of group exhibitions, did not suit my work. So I thought of a sort of archive that could present my work in the most comprehensive way. I decided I would include most of my work from 1993 onwards, and that I would add a 'book-work' section, that included new, not yet exhibited works. Later on I thought of adding an introductory section with works from 1980 to 1986 that had mostly been exhibited at the time, but had not been documented. MS - Your idea of collecting your work in an archive is very interesting, as is the idea of publishing almost all of it - and in one single volume. You have also published a significant amount of your work on the web (www.jacopobenci.com). What role does publication have for your work, both in print and on the web? JB - A book and a website are two utterly different things, each having its pros and cons. At the back of my book there is a section with brief biographies of the authors, but in my case I chose to include only my website details. My website includes a comprehensive biography and bibliography that I keep up to date, which wouldn't be possible with a book. On the other hand, I decided that my website would have a smaller selection of images compared to the book, which contains over three hundred and fifty pictures. MS - The format you chose - and the ample white margins surrounding the images - seems to me to be consistent with the ideas of Luigi Ghirri, who considered the book (rather than the exhibition) the ideal place for his work. Do you share his view? What function do white margins have in your book? JB - I bought Ghirri's first book, Kodachrome, in 1980 at the Rondanini Gallery in Rome, during his solo exhibition there. Each page of that book had a single image surrounded by an ample white space. The idea behind it was that an image needs a buffer area that establishes a pause, a silence, and focuses the viewer's attention. Other artists who were important for me especially at the beginning of my activity, such as Giulio Paolini and Ugo Mulas, did significant work with the book format. I also bought Mulas's La fotografia and Paolini's Idem in 1980. Jacopo Benci, Il mondo fluttuante, 1985

MS - The artists you mention were all engaged in distinctive processes of experimentation and reflection on their own art, though working in different fields, such as Arte Povera, 'conceptual' photography, avant-garde. How did their work influence your art, especially at the beginning? JB - In the summer of 1976, a friend of mine invited me to join him in Venice for the Film Festival. I then visited the Biennale and the Guggenheim Collection. In 1978 I went again to the Biennale, and I also visited the Venerezia / Rêvenice exhibition at Palazzo Grassi. My first encounter with conceptual art, installation, video, happened in an unmediated way. I had no knowledge of contemporary art, so my reaction was one of curiosity and wonder. It was rather like the experience of a child at the fairground: you are not able to understand the simple workings behind the hall of mirrors, the ghost train, the merry-go-round, the roller-coaster. They seem all the more fascinating because of their inexplicability. MS - Was it then that you developed an interest for photography? What attracted you to this medium in the early 1980s? Your book opens with the section 'Early works, 1980-86' which presents colour photographs of The floating world, showing images of a green, perfect, but uninhabited nature. There seems to me that there is a strong influence here of Ghirri's work, the early Ghirri of Paesaggi di cartone or the later Ghirri taking pictures of nature and gardens. Is that right? JB - When I was nineteen I had a friend who took black and white photographs, and printed them in his darkroom. I acted as his assistant. He had Ugo Mulas's book La fotografia. While he didn't make much of the Duchamp and 'Verifications' sections of that book, I was drawn to them. As I said, I visited the Venice Biennale for the first time in 1976. That included a large retrospective of the photographic works of Man Ray, who had just died. Then I discovered Ghirri's work at the exhibition L'immagine provocata at the 1978 Venice Biennale. There was a lot of photography-based conceptual art in those exhibitions. All these things had an influence on my decision to turn to visual art in 1978. In 1980 I bought a 35mm Nikon camera and set up my darkroom, but my idea was never to be a 'straight' photographer. I wanted to use photography to make art. My earlier black and white photography was in a sense 'conceptual', but the only work I have kept from that phase is Sguardo luminoso, with which my book opens and which I dated 1981-1993, because I made it in 1981 but I only found a title and a context for it in 1993. Il mondo fluttuante, the first photographic series that I exhibited in 1986, was a series of images of places. They were colour rather than B&W photographs, which shows, as you rightly noticed, the impact Ghirri's work had on me. MS - Your work strikes me for the fascination, the wonder towards external reality in its minimal details, as well as a listening approach. What role do these themes play in your artistic outlook? JB - The subject of my series Il mondo fluttuante, even if I wasn't fully aware of it at that time, is 'the garden' rather than 'nature'. This would become a deliberate reference in the 1990s with my photographic and video work from Itinerari silenziosi. I have lived in cities all my life, so for me the garden, the park, is something uncanny, a place that is usual yet not familiar. When a park is empty of people it may appear enigmatic because the place can feel haunted even if a human presence is not visible. There is an element of this in Antonioni's Blow Up... Eventually, I started to realize that the place, as it were, eludes the gaze that wants to grasp it in its entirety. It is necessary that the gaze should 'listen': its attitude has to be receptive, passive, rather than active, acquisitive. Sandro Bernardi, the author of the wonderful book Il paesaggio nel cinema italiano, had previously published an article entitled "Antonioni, il mistero del parco", where he wrote, «The park is an in-between zone, which simultaneously belongs to the city and is alien to it. A kind of border which sometimes is visible and at other times is not»[1]. The immediate reference is to Antonioni, but Baudelaire, Benjamin, Kracauer are also implied. One could expand on the idea of the 'in-between zone', of the 'Zwischenstellung', to include Ghirri and Celati's notion of the 'towards', in the sense of 'moving towards'. MS - Your choice of using video and super-8 film is also very interesting. Why did you choose this format and what were your aims in these works? JB - In 1978, when I was twenty-two, I applied to the course in directing at Rome's National Film School but was not successful. Over the next fifteen years, however, I watched the complete works of Bergman, Bresson, Tarkovsky, Paradzhanov, Kurosawa, Mizoguchi, Ozu, Buñuel, Vigo, Tati, Pasolini, Antonioni, and several others, as well as many silent films and many French, Russian, German avantgarde and experimental films. In 1995, alongside my photographic series entitled Itinerari silenziosi, I started to shoot some analogue video footage of the places I photographed. They were long, slow, close-up panning shots, partly inspired by some moments in Tarkovsky's films such as Stalker and Nostalghia. I made my first video piece, Sguardo luminoso I, at the end of 1996. In the case of the five 'luminous gaze' videos, I used video to portray stillness and silence rather than movement and the spoken word. This came from my interest in icons and Fayyum portraits and my reading of Lévinas, but also from directors such as Paradzhanov, whose film Sayat Nova I have always loved. In 1997 I borrowed a super-8 cine camera from a friend and shot a few reels using the now defunct Kodachrome 40 colour reversal film. I immediately decided that I would shoot a long feature on super-8 using both colour and B&W film stock and I bought two super-8 cameras. Most of my video works use a static camera, usually mounted on a tripod, whereas for the works on film (Itinerari silenziosi and Una giornata lunga senza io) I also used panning shots, long takes, and sometimes a hand-held camera. MS - Your work seems to revolve around pause, slowness, space, white, in consonance with Ghirri's poetics. What role do these themes play in your own poetics? To what extent do these themes seek to allow the viewer their own time to construct their own narrative, by establishing links between the images, aided by their own imagination? What role does imagination play in your work? JB - Pause, whiteness, space are essential things for me, just like slowness, and lingering. In Ghirri's work I found confirmation and support for such inclinations, which were also nourished by other things such as Far Eastern arts, especially Japanese art, that have always fascinated me. As a general rule, I do not provide 'explanations' for the titles I choose for my works. If somebody asks me where the titles come from, I have no problem in answering, but I do not think it is essential to provide a reference or explanation for each element of the work. I see explanation as a limitation of the spectator's indisputable right to interpretation. The point I am trying to make about withdrawing from an excess of information, explanation (justification, even?), is very exactly phrased by Tim Saunders in his text in my book – "we should leave our studies and our research centres behind and go out there for ourselves, attempting nothing, other than a simple 'being there' in silence". I am drawn to certain titles or phrases precisely because they bring with them a 'cluster' of meanings and cannot be pinned down to one. For instance, let's take the title of my book and my work cycle, Faraway and luminous. I found the phrase years ago in a monograph on the calligraphy and sumi paintings of Sengai, the 19th-century Japanese Zen master. Sengai was known all over Japan as a magisterial artist, and people went to him asking for the gift of a piece of calligraphy. One extant example bears only two ideograms, 'faraway' and 'luminous'. Sengai wrote the two characters and gave the piece of paper to the person who had asked him. No explanation. What is 'faraway and luminous'? Is it the moon, a shimmering lake on a plain, a spiritual creature? He didn't say, and the scroll does not give any indication. What is the relation between the phrase 'Faraway and luminous' and the images I collect under this title? I leave it to the viewer to decide. Maybe this is a way to answer your question about the role of imagination in my work. MS - How does your work relate to Luigi Ghirri's photographic work, and to Gianni Celati's poetics, in particular his interest in a 'simple' narration of space and in recovering the memory of places?

Jacopo Benci, Il mondo fluttuante, 1985

JB - I had the opportunity to hear Ghirri and Arturo Carlo Quintavalle talk in public at the Galleria Rondanini on 31 October 1980. I taped that lecture, and in 2002 I sent the transcript to the Ghirri Archive. During the lecture, Ghirri said, among other things: "My way of working does not aim at a 'beautiful photography' in the traditional sense, and it is certainly not meant to be 'ugly' either. What I tried to do is to use photography as a language, in which each element may not be on an equal footing with that which precedes or follows it, although, if taken individually, each one has its own validity. But their validity is reinforced in an overall view, seeing one work after the other. Some of the comments people made to me showed that, for instance, the works weren't read in a circular way, nor even in a linear way, that is, as a type of photography that is linked to art. This shows that people are not used to this, because exhibitions are generally meant to present an author's fifty best and most beautiful photographs, not connected to any context nor to one another except through a formal relationship, and that's it, the show is ready. I think this is a way to make and to conceive photography that I do not subscribe to; and I think this is clearly shown by the work I do". I am struck today by how the things Ghirri said, and which I could see in his work, had an influence on my own work later. For example the idea of working on a series of images in which, "although, if taken individually, each one has its own validity... their validity is reinforced in an overall view, seeing one work after the other"; and the idea of reading the works "in a circular way... even in a linear way, that is, as a type of photography that is linked to art". I certainly did not remember these words by Ghirri when I presented the first installation of my photographic series Itinerari silenziosi, in Verona in January 1997 and the following month in Rome. Yet, as can be seen in the installation shot on page 99 of my book, I picked up this idea of a circular reading of the works. I discovered much later the works by Celati that are closely related to Ghirri's. In January 2001 I went to Milan to see Leonardo's Last Supper, after which I chanced upon Luigi Ghirri's exhibition, Il profilo delle nuvole, at Palazzo delle Stelline. I spent the rest of the day, until closing time, in the Ghirri exhibition and bought the catalogue, the reissue of the 1989 volume published by Feltrinelli, where the texts by Celati work as accompaniment and counterpoint to Ghirri's images. Then I got hold of Voices from the Plains and Verso la foce and read them. They are books that I like very much and I have read them several times. Then I read "Conditions of light on the Via Emilia" (in the English translation, because Quattro novelle sulle apparenze is currently out of print). I like the idea of a 'simple' narrative, in a calm tone, of what Perec defined as the 'infra-ordinary'. In Je me souviens, Espèces d'espaces, L'infra-ordinaire, Perec is a city dweller. In Voices from the Plains and Verso la foce, Celati on the other hand wanders through small towns and villages, in the countryside, along riverbanks... But both share a sense of the need to record and give voice to things and places that are minute, minor, secluded, that seem to have no importance and no history, on the limit of visibility, on the edge of disappearance. I feel very sympathetic to the idea of a title such as Verso la foce, which echoes two of my favourite photographs by Ghirri, Verso Migliarino and Verso Lagosanto - two photos which show, so to speak, nothing: they certainly do not show Migliarino nor Lagosanto! This movement 'towards' ('verso') is for me a way to move along with the awareness that one never 'reaches' a place. I am thinking here of Aldo's wanderings in Antonioni's Il grido. And a passage from Michel de Certeau's The practice of everyday life, which I like very much: «To walk is to lack a place. It is the indefinite process of being absent and in search of a proper space»[2].

Jacopo Benci, still dal video Una giornata lunga senza io, 2004

MS - In his recent book, Architetture città visioni. Riflessioni sulla fotografia (2007), Gabriele Basilico sees literary inspiration as a common denominator for his generation of photographers, who grew up between the 1960s and 1970s, when photography was still seeking to establish itself as a discipline and as an art form in Italy. Among the favourite writers of his generation, he mentions Calvino and Celati, as well as Peter Handke. As a younger practitioner than Basilico, how do you assess his point of view? JB - Writers such as Calvino and Celati were certainly essential for artists / photographers of the generation of Ghirri and Basilico, but the opposite is also true: besides the case of Celati and Ghirri, I am thinking of Calvino and Giulio Paolini. There is, of course, the earlier, extraordinary example of Zavattini and Strand with Un paese. One should also include some Italian filmmakers in this network of references. A book like Voices from the Plains undoubtedly has a connection with Un paese, and the latter, in turn, with the Italian translation of Spoon River Anthology. But one cannot underestimate its link with Antonioni's Gente del Po, and the article that foreshadowed it, 'Per un film sul fiume Po', which Antonioni published in 1939. Moving forward in time, I would say the reflective wanderings of Verso la foce and Il profilo delle nuvole owe more than a little to images and atmospheres of Antonioni. I am also thinking here of Antonioni's short stories in That bowling alley on the Tiber. MS - Ghirri's way of combining experimentation with 'simplicity' and 'classicism' had a strong influence on contemporary photography. Several photographers and artists followed in his footsteps. What do you think of his influence, and how do you assess the works of his followers? JB - There is no doubt that Ghirri's work had a influence on contemporary photography, in Italy and elsewhere. Yet, it remains to be seen if Ghirri's followers really understood his teachings, or if they just drew formally on a certain way of photographing, whether interiors or landscapes, constructed images or merely 'captured' ones. There are many photographers-artists who work – in the wake of Ghirri – with 'landscape', but they usually do so in a predictable way, or worse, as a ready-made type of environmental and sociological survey. Imagine a local authority that wants to commission a nice documentation of their village, town or territory: wouldn't it be neat to get one or more photographers to make work 'in the style of Ghirri' and show it in a beautiful exhibition with a catalogue with 'scientific' and/or 'literary' texts about that place? The fact is that Ghirri did not quite think that way. In 1989 he wrote, «I would like this work on the Italian landscape to seem a bit like [...] an imprecise cartography, without compass points, more about the perception of a place than its cataloging or description, like a sentimental geography where the itineraries are not marked and precise, but obey the strange confusions of seeing»[3].

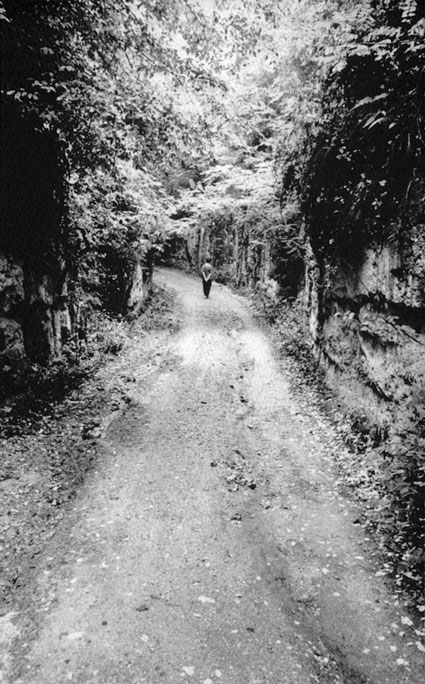

Jacopo Benci, Itinerari silenziosi, 1999

MS - In your view is there a dialogue between contemporary photography and literature, and, if so, how has it developed since the 1980s? What role did the collaboration between Ghirri and Celati and other artists in Viaggio in Italia play in establishing a closer dialogue between photography and literature? What do you think of the recent photo-book Viaggio in un paesaggio terrestre, by the photographer Vittore Fossati and the late writer Giorgio Messori, inspired by Ghirri? JB - The encounter and collaboration of Ghirri and Celati certainly prompted other collaborations between writers and artists/photographers, such as, for example, Viaggio in un paesaggio terrestre by Fossati and Messori. Their work brings to mind Ghirri and Celati's Il profilo delle nuvole, but it is also very different from it. In Viaggio in un paesaggio terrestre the prevalent aspect is a meditation on places, on their representation in images and words, and the proximity or distance between representation (I prefer the English word 'depiction', which implies the idea of 'portraying' and 'picture') and the place as it can be found now and there. I would say that in Viaggio in un paesaggio terrestre there is also a strong element of 'rêveries of the solitary wanderer', an emphasis on solitude (even if they travel together and meet other people during their journeys), and a certain melancholy. Their way of weaving fragments of other people's texts and images in their work also seems distant from Celati's approach, and quite close to certain texts and images by Ghirri, as well as to the recent literary practice of using of images in books, for instance, W.G. Sebald's Vertigo, Ulf Peter Hallberg's The Street Walker's Gaze, and Orhan Pamuk's Istanbul. MS - What is your relationship with places, especially the city where you live, and how do these places inspire your art? JB - I adopt what Baudelaire wrote in The painter of modern life, «To be away from home and yet to feel oneself everywhere at home; to see the world, to be at the centre of the world, and yet to remain hidden from the world», and «The spectator is a prince who everywhere rejoices in his incognito»[4]. Re-reading my old notebooks, I found out that already in 2002 I wrote: "As time goes by, I become more and more aware of the innumerable amount of nearby places, and, within each of them, corners and pockets of places, which you don't know but would like to know – which you think one should necessarily know. A movement that proceeds by way of constantly narrowing down the horizon, until one loses oneself in the immense and inexhaustible nature of what is, if not immediately contiguous, at least relatively close by: each corner of a city, each group of buildings bearing any interest, each little valley with an enigmatic rocky profile, each solitary grove, each isolated edifice in a boundless expanse, and many, many more things which one would never cease to enumerate".

Jacopo Benci, Itinerari silenziosi, 2006

MS - Much of your work seeems to me to based on a flâneur approach, or, to quote sociologist Giampaolo Nuvolati, a 'postmodern flâneur' approach (if one allows for this seeming contradiction, given that the image of the flâneur is essentially connected to modernism). According to Nuvolati, such an approach is characterized by an open-minded attitude towards the journey and nomadism, a fascination with the everyday and seemingly 'marginal' places, disenchantment towards contemporary society, a predisposition towards listening and reflection, and a penchant for wandering as a way of life. Do you subscribe to this form of relating to the outside world, or at least to some aspects of it? JB - Over the last few years, there has been a shift in my work towards a form of listening to places aimed more at the urban dimension. This is what recently urged me to read Giampaolo Nuvolati's book, Lo sguardo vagabondo. Il flâneur e la città da Baudelaire ai postmoderni (2006). I previously read other books that dealt with similar issues, such as Franco La Cecla's Perdersi and Contro l'architettura, and more recently Michael Jakob's Il paesaggio and Il giardino allo specchio. Percorsi tra pittura, cinema e fotografia. This is because, on one hand, I realized that it is problematic to think that one may have a real familiarity with the 'outside'; on the other hand, what Ghirri defined as the "explorations within a three-kilometre radius from home" are virtually endless. Claudio Magris wrote, "the known and the familiar, continuously discovered and enhanced, are the premise of encounter and adventure [...]. This also applies to places; the most fascinating journey is a return, an odyssey, and the places one usually walks through, the everyday microcosms travelled across over many years, are a Ulyssian challenge"[5]. In my explorations – no matter whether of a familiar place, like Rome, or an almost unknown one, such as, lately, Modena – I let myself be guided by the angle at which two streets meet, or by the view that is revealed, or promises to reveal itself, beyond a gate left ajar. MS - Do you agree with Nuvolati's view that flânerie is a form of 'resistance' toward the prevailing culture? JB - Yes, but maybe 'resistance' is also the unintentional resistance of places to the trend described by Gianni Celati at the end of Adventures in Africa: «in Europe [...] it is like being in a never-ending documentary, where one sees everything as clean, orderly, smooth, 'glossy', 'flashing', renovated. No difference is too striking, no car is too much of a wreck, no person is really toothless, no dress is really out of fashion, no shop is still decorated like five years ago, no shop window displays books that aren't the latest novelties. We wander around Paris and we see nothing but this other documentary of total novelty, where nothing is precarious any more, nothing is poor, decayed, makeshift, eaten by the wind, discarded by destiny. It is the documentary of global simulation, with no place, with no escape, which we are shown night and day for advertising purposes, through the glass screen we are supplied with for living around here»[6]. This 'resistance' exists not only in the form of the determined, intentional, planned actions of individuals, but also in the things themselves: all those things in Italian cities that are not "clean, orderly, smooth, 'glossy', 'flashing', renovated" and which, on the contrary, are – or bear traces of what is or was – "precarious, poor, decayed, makeshift, eaten by the wind, discarded by destiny". In my book there are many images in the sections Itinerari silenziosi and Lontano e luminoso (all belonging to places in cities) that are linked to these concerns. I have been trying to move forward lately, as I think may be seen in my blog Faraway & Luminous. I have reflected on what Nuvolati wrote about the transcription of the remarks made by those who observe the city from within. Over the last four years I have always been carrying a blank page notebook with me, in order to take notes about things I see wherever I am. I recently started to post some of those notes on my blog.

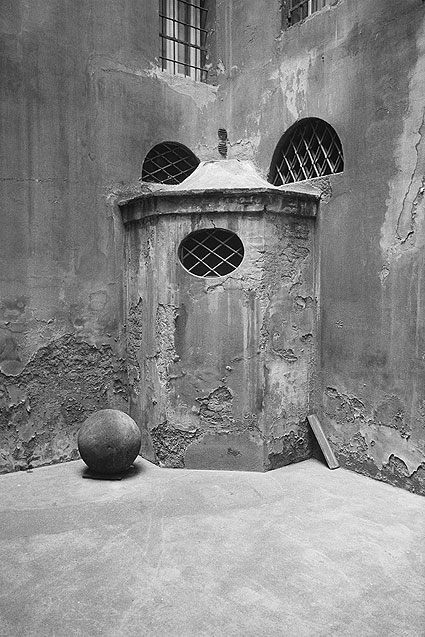

Jacopo Benci, Lontano e luminoso, 2007

MS - According to Nuvolati, the role of the flâneur implies a privileged social position, an elitist gaze. Do you agree with this definition, do you subscribe to it? JB - Nuvolati actually writes, "The flâneur's partiality is not only connected with gender, but also with class, level of education, ideological orientation, place of origin. He is very likely to belong to a middle-to-high income class, to have studied for many years or to have been in some way involved in the arts and sciences, to live in an affluent country and/or a big city. Nowadays, because of increased affluence, and therefore a higher level of education and more leisure time, flânerie is spreading, although it remains the prerogative of a restricted number of individuals who can practise it with continuity, and turn it into a cultural production. Therefore the vision of reality provided by the flâneurs will be affected by partiality; they will probe the territory with an elitist and in some way snobbish gaze. A gaze strongly biased not only by personal experiences, but also by the culture of their place of origin, and the values and political orientation of their class. Especially in late-modern society, where value codes tend to multiply, where the criteria of judgment appear evenly diversified and therefore weak, one witnesses the predominance of aesthetic over ethical reason"[7]. Although, broadly speaking, I belong to the category described by Nuvolati (from a socio-cultural perspective, I belong to the middle class, I had "an extended education" and have been "involved in the arts", I live in an affluent country and a big city), I belong nevertheless to a 'weak' category because I come from a white-collar, lower middle class family, and I live as a tenant in a peripheral neighbourhood. On the one hand, while my condition is undoubtedly 'exceptional' from a cultural point of view (I am the vice-director of a foreign academy, a visual artist as well as a practitioner of cultural studies), on the other hand it remains financially and socially unstable. Maybe it is this condition that led me – to use Nuvolati's terms – to "reject the standardized practices" of use and knowledge of the territory, and to explore possible "alternative patterns of interaction with places". I subscribe to a position of being on the margins – critically if not also geographically – vis-à-vis the 'centres' of the city. I have always practised "the refusal of time regimentations" and I have chosen part-time and freelance jobs. I would rather earn less in order to safeguard my 'emploi du temps'. When I was twenty, I was certainly helped in this respect by my discovery of Rimbaud and then Surrealist and Situationist views on labour. The "crossings of spatial boundaries" for me are crossings of temporal boundaries as well: outside ordinary hours, late at night for example, the city reveals another dimension (even the centre of Rome may be empty, almost as one can see it in films of the 1940s or 1950s) and, as Nuvolati says, these crossings become occasions to explore the city's interstices, which aren't necessarily peripheral, marginal, 'low', and can be discovered virtually anywhere. MS - What about Perec's book, Un homme qui dort [A man asleep], recently reissued in Italy by Quodlibet (2008), in Jean Talon's fine translation, with a preface by Gianni Celati? JB - Before reading the book, I saw the film of the same title, directed by Perec and Bernard Queysanne, and I felt a strong affinity with it. One thing I really liked about Un homme qui dort is the idea of 'wasting one's time' as a path towards a more profound and true way of discovering and discovering oneself. I think that the ideas derived from Baudelaire, Breton, Benjamin, Debord are joined here with Bataille's notion of 'expenditure', and maybe with a Zen-like attitude. Perec provides a real primer in 'wasting one's time': "Wanting nothing more. Waiting until there is nothing more to wait for. Wandering, sleeping. Letting oneself being taken by the crowd, by the streets. Following the sewage drains, the railings, the water along the riverbanks. Walking along the river, close to the walls. Wasting one's time. Steering clear of any plan, any itch. Having no desire, no resentment, no rebellion». And further on: «There are a thousand ways to kill time; no one resembles another, yet they are all the same, a thousand ways of not expecting anything [...]. You've got everything to learn, all those things one cannot learn, solitude, indifference, patience, silence. [...] You learn how to walk like a lonely man; how to stroll, to keep late hours, to see without looking, and to look without seeing. You learn transparence, immobility, non-existence. You learn how to be a shadow, and how to look at people as if they were stones"[8]. MS - Would you define your approach as a phenomenology of the everyday? JB - Between the late 1970s and the early 1980s I discovered Tarkovsky's Stalker – and its notion that the straight line is not the shortest way to proceed in a territory – and at the same time the Surrealist and Situationist texts on walking in the city without a predetermined destination, and being receptive to the call of seemingly meaningless places. I came back to these subjects from the 1990s onwards, I am more and more drawn towards what Henri Lefebvre in his Critique of everyday life defined as the 'discontinuities' in everyday life, the 'cracks' and 'tears' in the urban texture, which reveal «the uneven development which characterizes every aspect of our era»[9]. The filmmaker / architect Patrick Keiller dealt with that issue in his film London, which I first saw in London in 1994. When I saw it for the second time in December 2008, I had completely forgotten it, and I was struck to realize how strong a mark it had left on me. MS - In your view, what is the situation of contemporary Italian photography? What do you think are the main lines of research? What are the major problems that photography has to face nowadays? JB - The main problem of current photography is its uniformity and mediocrity. Lots of people mimic the styles of the 'stars' of the moment, whoever they may be. In Italy there are many followers of Ghirri who do landscape photography but, as I said before, most of their works are clichéd. With the advent of digital photography – which can be taken with still cameras, video cameras, cell phones – the production of images is enormous, but few of them are important and valuable. As was the case before digital photography, there are plenty of photos that are formally perfect, yet stereotyped and devoid of any thought. I myself do not follow what's currently being done very much, but I feel that if there is anything worthwhile out there that I do not know about yet, sooner or later I will come across it, maybe by chance. In January 2009 I went to the Bologna Art Fair, and visited all the gallery stands, one by one. I found only one interesting thing that I didn't already know: the photographs of Pentti Sammallahti. I checked him out and found that he has been long recognized as a master in Finland, but there isn't much available on his work. Apart from a few hard-to-find monographs, there is a small book in the Photo Poche series. I got hold of that and I found a miraculous statement by him, which I fully subscribe to: "the most important element in the work of a photographer is not creation or imagination, but the gaze and the willingness to do justice to what one sees. I realized then that one doesn't take photographs, one receives them".[10]

Jacopo Benci, Lontano e luminoso, 2009

Notes[1] Sandro Bernardi, "Antonioni, il mistero del parco", in M. Bertozzi (ed), Il cinema, l'architettura, la città, Rome: Editrice Dedalo, 2001 (English translation by J. Benci). [2] Michel de Certeau, The practice of everyday life, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1984, p. 103. [3] L. Ghirri, Paesaggio italiano/Italian landscape, Quaderni di Lotus/Lotus Documents, Electa, Milano, 1989; in L. Ghirri, W. Eggleston, G. Celant, P. Ghirri, E. Re, It's beautiful here, isn't it... Photographs and writings by Luigi Ghirri, Roma: Contrasto, 2008, p. 139. [4] C. Baudelaire, "The painter of modern life" (1863), transl. J. Mayne, in C. Harrison, P. Wood, J. Gaiger (eds), Art in theory, 1815-1900. An anthology of changing ideas, Oxford: Blackwell, 2003, p. 496. [5] C. Magris, L'infinito viaggiare, Milan: Mondadori, 2005, p. xxi, in G. Nuvolati, Lo sguardo vagabondo. Il flaneur e la città da Baudelaire ai postmoderni, Bologna: Il Mulino, 2006, p. 22.. [6] G. Celati, Avventure in Africa, Milan: Feltrinelli, 1998, pp. 178-79 (English translation by J. Benci. Cf. G. Celati, Adventures in Africa, translated by A. Bernardi, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2000). [7] G. Nuvolati, ibidem, pp. 124-25. [8] G. Perec, Un uomo che dorme, Macerata: Quodlibet, 2008, pp. 54-57 (English translation by J. Benci. Cf. G. Perec, Things: A Story of the Sixties & A Man Asleep, transl. by D. Bellos, A. Leak, Boston: David R. Godine / Verba Mundi, 2002). [9] H. Lefebvre, Critique of everyday life, II (1958), London: Verso, 1991, p. 8, in B. Highmore, Everyday life and cultural theory: an introduction, London: Routledge, 2002, p. 141. [10] Pentti Sammallahti, quoted by Gérard Macé, "Une pensée en images", in Pentti Sammallahti, Paris: Photo Poche/Actes Sud, 2007, p. 7 (English translation by Jacopo Benci). |

Jacopo Benci vive e lavora a Roma. Il suo lavoro comprende fotografia, video, film, installazione, performance; è stato esposto in gallerie e musei e presentato in festival video, in Italia, Argentina, Francia, Germania, Olanda, Gran Bretagna, Stati Uniti, Russia, Thailandia, Ungheria. La sua personale più recente, Sentieri invisibili, si è tenuta alla galleria Hybrida Contemporanea di Roma, 2010. Dal 1998 Jacopo Benci è Vicedirettore per le Arti Visive dell' Accademia Britannica, Roma. Marina Spunta - Iniziamo dal tuo recente volume dal titolo Jacopo Benci. Faraway and luminous, pubblicato nel 2007 dalla British School at Rome. In 400 pagine il volume presenta un'ampia sintesi del tuo lavoro dal 1980 al 2007 nel campo della fotografia, pittura, performance, video e film, oltre ad includere alcuni saggi critici sulla tua opera. Le opere presentate nel libro sono state in gran parte esposte in mostre e in numerose partecipazioni a rassegne e festival, in Italia e all'estero. Che scelte hai dovuto operare nella selezione del materiale per il libro? Jacopo Benci - L'idea di questo libro ha cominciato a prendere forma nel 2000. A partire dal 1993 il mio lavoro si è venuto articolando, prendendo forme diverse (fotografia, installazione, teatro, performance, video e film). La forma-catalogo, specie nel caso di esposizioni collettive, non si addiceva molto al mio lavoro. Ho pensato quindi di raccoglierlo in una sorta d'archivio che lo presentasse nel modo più esauriente possibile. Ho deciso che avrei incluso gran parte del mio lavoro dal 1993 in poi, e che ci sarebbe stata una sezione 'book-work' comprendente lavori nuovi e mai esposti. In un secondo momento ho pensato di aggiungere una sezione introduttiva, con lavori dal 1980 al 1986 che avevo per lo più esposto all'epoca, ma che non erano stati documentati. MS - È molto interessante l'idea di raccogliere il tuo lavoro in un archivio e anche di pubblicarlo quasi in toto - ed in un unico volume. Alla pubblicazione in volume si affianca quella sul web, che mi sembra anche molto esauriente (www.jacopobenci.com). Che importanza ha la pubblicazione su carta e in rete per il tuo lavoro? JB - Sono due cose assai diverse e hanno diversi vantaggi e svantaggi. In fondo al mio libro c'è una sezione con brevi biografie degli autori dei testi; per me si dà un rimando al mio sito web, dove c'è una pagina con la mia biografia e bibliografia che a differenza di quanto avviene per un libro può essere aggiornata. Viceversa, ho deciso che nel sito ci sarebbero state molte meno immagini che nel libro, che ne contiene oltre trecentocinquanta. MS - Il formato da te scelto - come pure gli ampi margini bianchi che circondano le immagini - mi sembra in consonanza con la poetica di Luigi Ghirri, che considerava il libro (prima che la mostra) il luogo ideale per la sua fotografia. È un'idea che condividi? Quale funzione ha il bianco nel tuo libro? JB - Comprai il primo libro di Ghirri, Kodachrome, alla Galleria Rondanini di Roma in occasione della sua personale nel 1980. Ogni pagina aveva una sola immagine con un grande spazio bianco attorno. L'idea era che un'immagine ha bisogno di una zona di rispetto, che stabilisca una pausa, un silenzio, e concentri l'attenzione. Altri artisti importanti per me soprattutto negli anni iniziali del mio lavoro, quali Giulio Paolini e Ugo Mulas, hanno avuto un rapporto essenziale con la forma-libro. Sempre nel 1980, mi procurai La fotografia di Mulas e Idem di Paolini.

Jacopo Benci, Itinerari silenziosi, 1997

MS - Gli artisti che citi – seppur in campi diversi, dall'arte povera alla fotografia 'concettuale' all'avanguardia - si distinguono per il marcato lavoro di sperimentazione e riflessione sulla loro arte. Che influenza hanno avuto sulla tua arte, soprattutto all'inizio? JB - Nell'estate del 1976, un amico m'invitò a raggiungerlo a Venezia per il Festival del Cinema. Una volta là, visitai anche la Biennale Arte e la Collezione Peggy Guggenheim. Lo stesso avvenne nel 1978, e visitai anche la mostra Venerezia / Rêvenice a Palazzo Grassi. I miei primi incontri con l'arte concettuale, le installazioni, il video avvennero senza mediazioni. Non avendo nessuna conoscenza dell'arte contemporanea, la mia reazione fu di curiosità e meraviglia. Un po' l'esperienza che si fa da bambini in un luna park: non si è in grado di capire i semplici congegni dietro il palazzo degli specchi, il tunnel del brivido, le giostre, l'ottovolante, che risultano dunque affascinanti soprattutto perché inesplicabili. MS - È in quegli anni che ti sei avvicinato alla fotografia? Che cosa ti ha portato a questo mezzo nei primi anni Ottanta? Il tuo volume si apre con "Early works, 1980-86", che presenta le fotografie a colori de Il mondo fluttuante, immagini di una natura molto verde, perfetta e spopolata. L'ispirazione qui mi sembra molto ghirriana, del primo Ghirri di Paesaggi di cartone o del Ghirri interessato più tardi alla natura e ai giardini. Che cosa pensi di questo mio accostamento? JB - A diciannove anni avevo un amico che fotografava in bianco e nero, e sviluppava e stampava in camera oscura. Gli facevo da assistente. Questo amico aveva anche il libro La fotografia di Mulas, ma mentre le "Verifiche" e la parte dedicata a Duchamp a lui non dicevano molto, io ne fui affascinato. Come ho già detto, la prima Biennale di Venezia che visitai fu quella del 1976, che comprendeva una grande retrospettiva di Man Ray, appena scomparso; alla Biennale 1978 poi scoprii l'opera di Ghirri nella mostra L'immagine provocata. In quelle Biennali c'era molta arte concettuale che faceva uso della fotografia. Tutte queste cose furono importanti per me, quando presi definitivamente la strada dell'arte nel 1978. Nel 1980 comprai una Nikon 35mm e misi su una piccola camera oscura, ma fin da subito la mia idea non era di fare il fotografo, bensì di usare la fotografia per fare lavoro artistico. Feci subito dei lavori fotografici in bianco e nero più o meno 'concettuali', di cui l'unico superstite è lo Sguardo luminoso che apre il mio libro e che ho datato 1981-1993, perché è un lavoro del 1981 ma ha trovato un titolo e un contesto solo dodici anni dopo. Peraltro il primo lavoro fotografico che abbia esposto, Il mondo fluttuante, nel 1986, era una serie di immagini di luoghi, a colori, il che mostra – come noti giustamente – l'impatto su di me del lavoro di Ghirri. MS - Il tuo lavoro colpisce per la meraviglia, lo stupore verso la realtà esterna, percepita nei minimi dettagli, come pure l'ascolto. Che ruolo hanno questi temi nella tua poetica? JB - Anche se all'epoca non ne ero del tutto consapevole, il tema delle fotografie de Il mondo fluttuante è, più che la 'natura', quello del 'giardino'. Questo tema divenne consapevole in me negli anni Novanta con le fotografie e i video Itinerari silenziosi. Io ho sempre vissuto in città e il giardino, il parco, è qualcosa di 'unheimlich', di consueto e insieme non familiare. Quando è spopolato può diventare enigmatico perché il fatto che sia privo di presenze umane non lo rende meno abitato, nel senso di 'hanté'. È un po' l'idea che si trova in Blow-Up di Antonioni... A un certo punto, poi, ho cominciato a rendermi conto che il luogo, per così dire, sfugge allo sguardo che vuole com-prenderlo. Bisogna che lo sguardo 'ascolti': che sia ricettivo, passivo, piuttosto che attivo, acquisitivo. Sandro Bernardi, autore del bellissimo libro Il paesaggio nel cinema italiano, aveva precedentemente pubblicato un saggio intitolato "Antonioni, il mistero del parco", dove tra l'altro scrive: «Il parco è una zona incerta, che fa parte della città e, allo stesso tempo, non ne fa parte. Una specie di confine che a volte si vede e a volte non si vede»[1]. Il riferimento immediato è Antonioni ma in filigrana ci sono Baudelaire, Benjamin, Kracauer... E si potrebbe ampliare quest'idea della 'zona incerta', della 'Zwischenstellung', anche all'accezione in Ghirri e Celati del 'verso', nel senso di 'andare verso'. MS - È molto interessante anche la scelta di lavorare con video e film super-8. Perché questa scelta e che cosa ti proponevi con questi lavori? JB - Nel 1978, a ventidue anni, tentai di farmi ammettere al corso di regia del Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia. Nei successivi quindici anni, comunque, vidi intere filmografie di registi come Bergman, Bresson, Tarkovskij, Paradzhanov, Kurosawa, Mizoguchi, Ozu, Buñuel, Vigo, Tati, Pasolini, Antonioni e altri, oltre a molto cinema muto e a film sperimentali e delle avanguardie francese, russa e tedesca. Nel 1995, mentre stavo sviluppando la serie fotografica Itinerari silenziosi, iniziai a fare delle riprese video nei luoghi dove fotografavo. Erano panoramiche ravvicinate, il più possibile lunghe e lente, in parte ispirate da momenti di film tarkovskiani quali Stalker e Nostalghia. Alla fine del 1996 realizzai il mio primo lavoro video, Sguardo luminoso I. Nel caso dei cinque video Sguardo luminoso, usai il video per raffigurare l'immobilità e il silenzio piuttosto che il movimento e la parola. Questo era legato al mio interesse per le icone e i ritratti del Fayyum, e la mia lettura di Lévinas, ma anche da un regista come Paradzhanov, di cui ho sempre amato il film Sayat Nova. Nel 1997 presi in prestito da un amico una cinepresa super-8 e girai qualche bobina con la pellicola invertibile Kodachrome 40, oggi non più prodotta. Decisi subito che avrei girato un film di lunga durata in super-8 usando pellicola in bianco e nero e a colori, e comprai due cineprese super-8. Nella maggior parte delle mie opere video la telecamera è statica, di solito su treppiede, mentre nei film (Itinerari silenziosi e Una giornata lunga senza io) uso anche panoramiche, piani sequenza, e talvolta la camera a mano. MS - Il tuo lavoro sembra improntato alla pausa, la lentezza, lo spazio, il bianco, in consonanza con la poetica di Ghirri. Che ruolo hanno questi temi nella tua poetica? Sono mezzi per lasciare al lettore il proprio tempo di visione, ovvero il tempo per costruire una narrazione stabilendo nessi fra le immagini anche grazie alla propria immaginazione? Che ruolo ha l'immaginazione nel tuo lavoro? JB - La pausa, il bianco, lo spazio, sono per me essenziali, così come la lentezza e l'indugio. In Ghirri ho trovato conferma e sostegno per queste mie inclinazioni, che si sono però nutrite anche di altro, per esempio le arti dell'Estremo Oriente, e in particolare il Giappone, che mi ha sempre interessato. In linea generale, non fornisco 'spiegazioni' dei miei lavori o dei titoli che scelgo per essi. Non ho difficoltà a rispondere se qualcuno mi pone una domanda al riguardo, ma non penso che sia essenziale fornire, diciamo così, preventivamente riferimenti o spiegazioni per ogni elemento del lavoro. Fare ciò mi parrebbe una limitazione dell'irrinunciabile diritto dello spettatore all'interpretazione. Quello che sto cercando di dire a proposito dell'evitare l'eccesso d'informazione, spiegazione (fors'anche giustificazione), è espresso molto esattamente da Tim Saunders in un passo del suo testo nel mio libro - «dovremmo lasciare i nostri studi e centri di ricerca alle spalle e andar laggiù per noi stessi, tentando null'altro che un semplice 'esserci' in silenzio». MS - Che rapporto c'è tra il tuo lavoro e la fotografia di Luigi Ghirri e la poetica di Gianni Celati, in particolare il suo interesse per una narrazione 'semplice' dello spazio e per il recupero della memoria dei luoghi?

Jacopo Benci, still dal film Itinerari silenziosi, 2002

JB - Ebbi modo di ascoltare Ghirri e Arturo Carlo Quintavalle parlare in pubblico alla Galleria Rondanini il 31 ottobre 1980. Registrai la conversazione, di cui ho inviato la trascrizione nel 2002 all'Archivio Ghirri. In quell'occasione, Ghirri disse tra l'altro: «Il mio modo di lavorare non tende ad una 'bella fotografia' nel senso tradizionale, né certamente intende essere una fotografia 'brutta'. Io ho cercato di fare, di usare la fotografia come un linguaggio, quindi come tale suscettibile anche che ogni singola parte del linguaggio non sia alla stessa altezza di quella che l'ha preceduta e di quella seguente, anche se prese singolarmente hanno una loro validità; ma la loro validità è maggiormente rafforzata in una visione d'insieme, lavoro per lavoro. Io, parlando con alcune persone, sentivo alcuni commenti: per esempio, è stata notata poco una lettura non dico circolare, ma almeno lineare dei lavori, cioè di una fotografia legata all'arte; eppure c'è proprio una disabitudine, proprio perché con le altre mostre si intende dare di un autore le cinquanta fotografie meglio riuscite, più belle, slegate da qualsiasi contesto e l'una dall'altra se non per una relazione di forma, e la mostra di fotografia è già fatta. Io penso che questo sia un modo di fare e di concepire la fotografia che non condivido; e penso si veda ovviamente dal lavoro che faccio». Mi colpisce oggi quanto queste cose che Ghirri disse – e che riscontravo nel suo lavoro – abbiano poi avuto un influsso sul mio lavoro: ad esempio l'idea di lavorare per serie di immagini che «anche se prese singolarmente hanno una loro validità; ma la loro validità è maggiormente rafforzata in una visione d'insieme, lavoro per lavoro»; e l'idea di «una lettura non dico circolare, ma almeno lineare dei lavori, cioè di una fotografia legata all'arte». Certamente non ricordavo coscientemente queste parole di Ghirri quando nel 1997 presentai la prima installazione delle mie fotografie Itinerari silenziosi, a Verona in gennaio e a Roma in febbraio. Ma come si può vedere dall'immagine a pagina 99 del mio libro, riprendevo – letteralmente – l'idea di «una lettura circolare [...] dei lavori». Quanto all'opera di Celati più strettamente legata con Ghirri, l'ho scoperta molto più tardi. Nel gennaio 2001 andai a Milano per visitare il Cenacolo di Leonardo, e dopo che ne fui uscito m'imbattei nella mostra Luigi Ghirri, Il profilo delle nuvole al Palazzo delle Stelline. Restai nella mostra fino all'ora della chiusura e presi il catalogo, che era la ristampa del volume Feltrinelli del 1989, con i testi di Celati che accompagnano e fanno da controcanto alle immagini di Ghirri. Letti quelli, cercai e lessi Narratori delle pianure e Verso la foce. Sono libri che amo molto e che ho letto più volte. Ho poi letto "Condizioni di luce sulla via Emilia" nella traduzione inglese, perché Quattro novelle sulle apparenze è attualmente esaurito. Amo l'idea della narrazione 'semplice', in tono pacato, di quello che Perec definisce 'infra-ordinario'. In Je me souviens, Espèces d'espaces, L'infra-ordinaire Perec è un abitatore della città, mentre Celati, in Narratori delle pianure e Verso la foce, vaga attraverso borghi e villaggi, nelle campagne, presso argini di fiume... ma hanno in comune il senso della necessità di registrare e dar voce a cose e luoghi minuti, minori, appartati, apparentemente senza importanza e senza storia, al limite della visibilità, sull'orlo della scomparsa. Sento molto vicina l'idea di un titolo come Verso la foce, che richiama due fotografie di Ghirri che amo molto, Verso Migliarino e Verso Lagosanto - due foto in cui non si vede, per così dire, nulla: certamente non Migliarino né Lagosanto! Questo muoversi 'verso' è per me un procedere con la consapevolezza che non si giunge 'a'. Penso ai vagabondaggi di Aldo ne Il grido di Antonioni. E a un passo de L'invention du quotidien di Michel de Certeau che mi è molto caro: «Camminare significa esser privi di luogo. È il processo indefinito dell'essere assenti e in cerca di uno spazio proprio» («Marcher, c'est manquer d'un lieu. C'est le procès indéfini d'être absent et en quête d'un propre»).[2]

Jacopo Benci, Itinerari silenziosi, 2007

MS - Nel suo recente libro Architetture città visioni. Riflessioni sulla fotografia (2007) Gabriele Basilico ritiene l'ispirazione letteraria il denominatore comune della sua generazione di fotografi, cresciuti negli anni Sessanta / Settanta, quando la fotografia cercava ancora di affermarsi come arte e disciplina in Italia. Fra gli scrittori preferiti della sua generazione, egli cita Calvino e Celati, oltre che Peter Handke. Sebbene tu sia più giovane, che cosa pensi della posizione di Basilico? JB - Scrittori come Calvino e Celati sono stati certamente essenziali per artisti/fotografi della generazione di Ghirri e Basilico, ma è stato vero anche il contrario: oltre al caso di Celati e Ghirri, penso a Calvino e Giulio Paolini. Più indietro, naturalmente, c'è il precedente straordinario di Un paese di Zavattini e Strand. Bisogna tenere anche certi autori del cinema italiano all'interno di questa rete di rimandi. Se Narratori delle pianure ha certamente un legame con Un paese e questo, a sua volta, con la traduzione dell'Antologia di Spoon River, non si può trascurare di metterlo in relazione anche con Gente del Po di Antonioni e all'articolo che lo prefigurava, "Per un film sul fiume Po" che Antonioni pubblicò nel 1939. E continuando in avanti nel tempo, i vagabondaggi pensosi di Verso la foce e Il profilo delle nuvole devono, credo, più che qualcosa a immagini e atmosfere antonioniane. Penso anche all'Antonioni narratore di Quel bowling sul Tevere. MS - Ghirri ha avuto una forte influenza sulla fotografia contemporanea nel combinare sperimentazione a 'semplicità' e 'classicità'. Vari fotografi e artisti hanno seguito la sua scia. Che cosa pensi della sua influenza e dell'opera dei suoi seguaci? JB - L'opera di Ghirri ha senz'altro avuto un'influenza sulla fotografia contemporanea, in Italia e non solo, ma resta da vedere se chi ha cercato di seguire i suoi passi ha veramente compreso la sua lezione o si sia limitato a riprendere formalmente un certo modo di lavorare, che si tratti di interni o di esterni, di immagini costruite o semplicemente 'catturate'. Ci sono numerosi fotografi-artisti che lavorano – sulla scia di Ghirri – sul tema del 'paesaggio', ma di solito in maniera prevedibile e, peggio, come forma bell'e pronta di rilievo ambientale e sociologico. Immaginiamo un'amministrazione locale che voglia far fare un bel servizio sul proprio paese, cittadina o territorio: cosa c'è di meglio di chiamare uno o più fotografi a fare un lavoro 'alla Ghirri', farne una bella mostra corredata di catalogo con scelta di scritti 'scientifici' e/o 'letterari' sul quel territorio? Il fatto è che Ghirri non ragionava in questo modo. Ghirri scriveva nel 1989: «Questo lavoro sul paesaggio italiano vorrei che apparisse un po' così [...], una cartografia imprecisa, senza punti cardinali, che riguarda più la percezione di un luogo che non la sua catalogazione o descrizione, come una geografia sentimentale dove gli itinerari non sono segnati e precisi, ma ubbidiscono agli strani grovigli del vedere»[3].

Jacopo Benci, Itinerari silenziosi, 2006

MS - Secondo te, esiste un dialogo fra fotografia e letteratura italiana contemporanea, e, se sì, che forme ha preso a partire dagli anni Ottanta? Che importanza ha avuto a riguardo la collaborazione tra Ghirri e Celati e altri artisti a Viaggio in Italia? E cosa pensi del recente fotolibro, di ispirazione ghirriana, Viaggio in un paesaggio terrestre, del fotografo Vittore Fossati e dello scrittore purtroppo scomparso Giorgio Messori? JB - L'incontro e la collaborazione fra Ghirri e Celati ha certamente stimolato forme di collaborazione fra scrittori e artisti/fotografi, come mostra, ad esempio, Viaggio in un paesaggio terrestre di Fossati e Messori. La loro operazione richiama quella di Ghirri e Celati in Il profilo delle nuvole, ma è insieme molto diversa. Preponderante in Viaggio in un paesaggio terrestre è l'aspetto di meditazione sui luoghi, sulla loro rappresentazione visiva o verbale, e sulla vicinanza o sullo scarto fra la rappresentazione (qui aiuterebbe usare il termine inglese 'depiction', che contiene l'idea di 'raffigurare' e di 'immagine') e il luogo così come lo si ritrova ora e là. Inoltre il motivo delle 'rêveries du promeneur solitaire' mi pare molto marcato, così come l'accento sulla solitudine (pur viaggiando in due e pur incontrando altre persone durante i viaggi) e su una certa melanconia. L'intessere nella propria opera frammenti di testi e immagini altrui mi sembra anche distante dal modo di Celati, e se mai più vicino agli scritti e a certe immagini di Ghirri, oltre che a un certa pratica letteraria recente, penso all'uso delle immagini in libri come Vertigini di W.G. Sebald, Lo sguardo del flâneur di Ulf Peter Hallberg, e Istanbul di Orhan Pamuk. MS - Qual è il tuo rapporto con i luoghi e in particolare con la città in cui vivi, e come questi luoghi ispirano la tua arte? JB - Faccio mio quanto Baudelaire scriveva nel Peintre de la vie moderne: «essere fuori di casa, e ciò nondimeno sentirsi ovunque nel proprio domicilio; vedere il mondo, esserne al centro e restargli nascosto»; e ancora, «l'osservatore è un principe che gode ovunque dell'incognito»[4]. Rileggendo i miei taccuini, vedo che già nel 2002 scrivevo: «Più passa il tempo e più ci si rende conto dell'innumerabile quantità di luoghi vicini e vicinissimi, e, al loro interno, di angoli e sacche ('pockets') di luoghi, che non si conoscono ma che si vorrebbe conoscere – che si pensa si dovrebbero necessariamente conoscere. Un movimento che procede per progressivi restringimenti di orizzonte, fino a perdersi nell'immensità e nell'inesauribilità di ciò che è, se non immediatamente contiguo, per lo meno relativamente vicino: ogni angolo di città, ogni gruppo di edifici di un qualche interesse, ogni piccola valle dai profili rocciosi enigmatici, ogni boschetto solitario, ogni architettura isolata in una campagna sconfinata, e molto, molto altro ancora che non si finirebbe mai di enumerare».

Jacopo Benci, Itinerari senza io, 2007

MS - Molto del tuo lavoro mi sembra impostato su un approccio da flâneur, o meglio, per usare un termine del sociologo Giampaolo Nuvolati, da 'flâneur postmoderno' (se è permessa questa apparente contraddizione in termini, visto che l'immagine del flâneur è essenzialmente legata al modernismo). Secondo Nuvolati questo approccio si distingue per un'apertura al viaggio e al nomadismo, un incanto per il quotidiano e per luoghi apparentemente 'marginali', un disincanto per la società contemporanea, una predisposizione per l'ascolto e la riflessione, e una predilezione per il camminare come filosofia di vita. Ti riconosci in questo approccio o in alcune di queste modalità di relazionarsi all'esterno? JB - Nel mio lavoro degli ultimi anni c'è stato uno spostamento verso un ascolto dei luoghi rivolto maggiormente alla dimensione urbana. Questo mi ha spinto a leggere il libro di Giampaolo Nuvolati, Lo sguardo vagabondo. Il flâneur e la città da Baudelaire ai postmoderni (2006). Avevo fatto in precedenza altre letture in questa direzione: Perdersi e Contro l'architettura di Franco La Cecla, più recentemente Il paesaggio e Il giardino allo specchio. Percorsi tra pittura, cinema e fotografia di Michael Jakob. Ciò è avvenuto anche per il rendermi conto, da una parte, che pensare di avere vera familiarità con il 'fuori' è problematico; e dall'altra, che le «esplorazioni a non più di tre chilometri da casa propria» di cui parlava Ghirri sono virtualmente inesauribili. Come scrive Claudio Magris, «il noto e il familiare, continuamente scoperti e arricchiti, sono la premessa dell'incontro e dell'avventura [...]. Ciò vale pure per i luoghi; il viaggio più affascinante è un ritorno, un'odissea, e i luoghi del percorso consueto, i microcosmi quotidiani attraversati da tanti anni, sono una sfida ulissiaca»[5]. Nelle mie esplorazioni – non importa se in un luogo a me familiare, come Roma, o quasi sconosciuto come ad esempio, ultimamente, Modena – mi lascio guidare dall'angolo con cui una strada ne interseca un'altra, o dalla veduta che si rivela, o promette di rivelarsi, oltre un portone socchiuso. MS - Condividi l'idea di Nuvolati che quella del flâneur è una posizione di 'resistenza' alla cultura imperante? JB - Sì, ma forse la 'resistenza' è anche quella inintenzionale dei luoghi alla tendenza descritta da Gianni Celati nel finale di Avventure in Africa: «in Europa [...] è come essere in un documentario perpetuo, dove vedi tutto pulito, ordinato, levigato, glossy, flashing, rifatto a nuovo, neanche uno scarto troppo vistoso, una macchina troppo squinternata, una persona veramente sdentata, un vestito davvero fuori moda, un negozio che sia rimasto come cinque anni fa, una vetrina con libri che non siano novità assolute. Andiamo in giro per Parigi e vediamo soltanto quest'altro documentario del nuovo totale, senza più niente di precario, di povero, decaduto, rimediato, tarlato dal vento, scartato dal destino. È il documentario della simulazione globale, senza luogo, senza scampo, che ci mostrano a titolo pubblicitario notte e giorno, dietro lo schermo di vetro che abbiamo in dotazione per vivere da queste parti»[6]. Questa 'resistenza' dunque non è soltanto in azioni determinate, intenzionali, pianificate compiute da individui, ma è anche nelle cose: in tutto ciò che nelle città italiane continua a non essere «pulito, ordinato, levigato, glossy, flashing, rifatto a nuovo» e viceversa ad essere – o a recar tracce di ciò che è o era – «precario, povero, decaduto, rimediato, tarlato dal vento, scartato dal destino». Nel mio libro, le immagini legate a questo ordine di pensieri, tutte relative a luoghi nelle città, si trovano nelle sezioni Itinerari silenziosi e Lontano e luminoso. Ma attualmente sto cercando di andare un po' oltre, come penso si possa vedere nel mio blog Faraway & Luminous. Ho riflettuto su quanto Nuvolati scrive riguardo alla messa in scrittura delle osservazioni che compie chi guarda la città dal suo interno. Negli ultimi quattro anni ho preso l'abitudine di portare sempre con me un taccuino a fogli bianchi, per poter raccogliere appunti su quanto vedo là dove mi trovo. Ho iniziato da poco a trascrivere sul mio blog alcune di queste annotazioni. Jacopo Benci, Itinerari silenziosi, ©2006

MS - La figura del flâneur, secondo Nuvolati, implica anche una posizione sociale privilegiata, uno sguardo elitario. Sei d'accordo con questa definizione e ti riconosci in essa? JB - In effetti Nuvolati scrive: «La parzialità del flâneur non riguarda però solo il genere, ma anche la classe sociale, il livello di educazione, l'orientamento ideologico, il luogo di origine. È infatti assai probabile che egli appartenga a un ceto medio-alto, che abbia seguito un prolungato percorso di studi o comunque frequentato le arti o le scienze, che provenga da un paese ricco e/o da una grande città. Se oggi, grazie all'innalzamento complessivo del benessere, e dunque alla maggiore istruzione e alla crescente disponibilità di tempo libero, la flânerie si sta diffondendo, resta pur sempre un ristretto gruppo di individui a potersi permettere di praticarla con continuità, fino a trasformarla in prodotti culturali. La visione della realtà offerta dai flâneur soffrirà, dunque, di parzialità; sarà uno sguardo ancora elitario e per certi versi snobistico a scandagliare il territorio. Uno sguardo fortemente condizionato non solo dalle esperienze personali, ma anche dalla cultura del paese di provenienza, dai valori e dagli orientamenti politici della classe di appartenenza. Soprattutto nella società tardomoderna, dove i codici valutativi tendono a moltiplicarsi, dove i criteri di giudizio risultano ugualmente diversificati e pertanto deboli, si assiste al prevalere della ragione estetica su quella etica»[7]. Se non posso non inserirmi in linea generale nella categoria descritta da Nuvolati (appartengo socio-culturalmente al ceto medio, ho seguito «un prolungato percorso di studi» e ho «frequentato le arti», provengo da un paese ricco e da una grande città), appartengo però a una categoria 'debole' in quanto provengo da una famiglia di piccolissima borghesia impiegatizia e vivo in affitto in un quartiere periferico. La mia condizione, se da un lato è di indubbia 'eccezionalità' sotto il profilo culturale (vicedirettore di una accademia straniera, attivo nelle arti visive ma anche negli studi culturali), dall'altro resta finanziariamente e socialmente 'non garantita'. Forse è questa condizione che mi porta – per usare i termini di Nuvolati – a «rifiutare le pratiche massificanti» della fruizione e della conoscenza del territorio e a esplorare possibili «modelli alternativi di interazione con i luoghi». Mi riconosco in una posizione di marginalità – critica se non anche geografica – rispetto ai 'centri' della città. Da sempre ho praticato «il rifiuto dei regimi orari» e mi sono indirizzato verso lavori part-time e freelance, preferendo guadagnare meno ma salvaguardare il mio 'emploi du temps', e in questo certamente la scoperta, quando avevo poco più di vent'anni, prima di Rimbaud e poi delle posizioni surrealiste e situazioniste verso il lavoro mi ha aiutato. Gli «sconfinamenti spaziali» sono per me anche sconfinamenti temporali: fuori dagli orari 'consueti', ad esempio a tarda notte, la città si rivela in un'altra dimensione (perfino il centro di Roma può essere deserto, quasi come lo si vede nei film degli anni Quaranta o Cinquanta) e, come dice Nuvolati, questi sconfinamenti divengono allora occasioni per esplorare la città nei suoi interstizi che non sono necessariamente periferici, marginali, 'bassi' ma possono essere trovati virtualmente ovunque. MS - E che cosa pensi del libro di Perec, Un uomo che dorme, di recente ripubblicato da Quodlibet (2008) in una bella traduzione di Jean Talon e con una prefazione di Gianni Celati? JB - Prima di leggere il libro, avevo visto l'omonimo film di Perec e Bernard Queysanne che ho sentito molto vicino alla mia sensibilità. Ciò che ho amato molto in Un uomo che dorme è l'idea del 'perdere tempo' come strada verso un più profondo e vero trovare e trovarsi. Qui le idee di Baudelaire, Breton, Benjamin, Debord si uniscono, mi sembra, alla 'dépense' batailliana, e forse a suggestioni zen. Perec dà del perder tempo un vero e proprio breviario: «Non voler più niente. Aspettare finché non ci sia più niente da aspettare. Vagare, dormire. Lasciarsi portare dalla folla, dalle vie. Seguire i canaletti di scolo, le inferriate, l'acqua lungo le sponde. Camminare lungo il fiume, rasente ai muri. Perdere tempo. Tenersi lontano da ogni progetto, da ogni smania. Essere senza desideri, senza risentimenti, senza ribellione». E più oltre: «Ci sono mille modi di ammazzare il tempo, nessuno che si somigli, però tutti si equivalgono, mille maniere di non aspettare niente [...]. Hai tutto da imparare, tutto quello che non si può imparare: la solitudine, l'indifferenza, la pazienza, il silenzio. [...] Impari a camminare da uomo solo, ad andare a zonzo, a tirar tardi, a vedere senza guardare, e a guardare senza vedere. Impari la trasparenza, l'immobilità, l'inesistenza. Impari a essere un'ombra e a guardare gli uomini come se fossero pietre»[8]. MS - Definiresti il tuo approccio una fenomenologia del quotidiano? JB - Tra fine anni Settanta e inizio anni Ottanta scoprii più o meno simultaneamente Stalker di Tarkovskij – con la sua idea che per procedere in un territorio la linea retta non è la via più breve – e i testi surrealisti e situazionisti relativi al camminare nella città senza una meta predeterminata e all'essere sensibili al richiamo di luoghi apparentemente insignificanti. Sono ritornato su queste tematiche dagli anni Novanta in poi, e sono sempre più attratto da quelle che Henri Lefebvre definiva nella Critica della vita quotidiana le 'discontinuità' nella vita quotidiana, le 'crepe' e gli 'strappi' nel tessuto urbano che rivelano «lo sviluppo ineguale» che «resta la grande legge del mondo moderno»[9]. Questo è qualcosa di cui parla anche il filmmaker e architetto Patrick Keiller nel suo film London. Lo vidi per la prima volta a Londra nel 1994. L'ho visto per la seconda volta solo a dicembre 2008, e sono rimasto colpito nel rendermi conto quanto quel film, che avevo completamente dimenticato, avesse lasciato una forte impronta in me. MS - Qual è la situazione della fotografia italiana attuale? Quali sono, secondo te, le principali linee di ricerca? Quali sono i maggiori problemi che la fotografia deve affrontare oggi? JB - Il problema maggiore della fotografia attuale è la sua uniformità e medietà. Molti emulano più o meno bene gli stili dei 'nomi' del momento, quali che siano. In Italia c'è una linea che si ispira a Ghirri e alla fotografia di paesaggio, ma come ho detto prima tende ad esser di maniera. Soprattutto con l'avvento della fotografia digitale, che si fa con macchine fotografiche, telecamere, telefoni cellulari, la produzione di immagini è immensa, ma le cose importanti e valide sono poche. C'è, come già prima della fotografia digitale, un'abbondanza di fotografie formalmente perfette, ma stereotipate e prive di pensiero. Personalmente non seguo l'attualità più di tanto, ma sento che se c'è qualcosa di interessante che non conosco in qualche modo, per vie anche casuali, prima o poi lo scoprirò. A gennaio 2009 ero all'Arte Fiera di Bologna, e ho visitato tutti gli stand delle gallerie, uno per uno. Una sola cosa mi ha interessato fra quelle che già non conoscevo: le fotografie di Pentti Sammallahti. Ho indagato e ho scoperto che è considerato da tempo un maestro in Finlandia, ma sul suo lavoro c'è solo qualche monografia di scarsa reperibilità, e un libretto della serie Photo Poche, che ho comprato, e in cui ho trovato una sua frase miracolosa, che condivido in pieno: «l'élément le plus important du travail d'un photographe n'est pas la création ni l'imagination, mais le regard et la volonté de rendre justice à ce qu'on voit. J'ai alors compris qu'on ne prenait pas les photographies, mais qu'on les recevait».[10]

Jacopo Benci, Lontano e luminoso, ©2009

Note[1] Sandro Bernardi, "Antonioni, il mistero del parco", in M. Bertozzi (ed), Il cinema, l'architettura, la città, Roma: Editrice Dedalo, 2001. [2] Michel de Certeau, L'invenzione del quotidiano, Roma: Edizioni Lavoro, 2005, p.158. Il passo originale è in Michel de Certeau, L'invention du quotidien. I. Arts de faire, Parigi: Gallimard, 1990, p. 155. [3] L. Ghirri, Paesaggio italiano/Italian landscape, Quaderni di Lotus/Lotus Documents, Electa, Milano, 1989; ora in L. Ghirri, W. Eggleston, G. Celant, P. Ghirri, E. Re, Bello qui, non è vero? Fotografie e testi di Luigi Ghirri, Roma: Contrasto, 2008, p. 139. [4] C. Baudelaire, "Il pittore della vita moderna" (1863), in C. Baudelaire, Opere, a cura di G. Raboni e G. Montesano, Milano: Mondadori, 1996, p. 1282. [5] C. Magris, L'infinito viaggiare, Milano: Mondadori, 2005, p. xxi, cit. in G. Nuvolati, Lo sguardo vagabondo. Il flâneur e la città da Baudelaire ai postmoderni, Bologna: Il Mulino, 2006, p. 22. [6] G. Celati, Avventure in Africa, Milano: Feltrinelli, 1998, pp. 178-79. [7] G. Nuvolati, ibidem, pp. 124-25. [8] G. Perec, Un uomo che dorme, Macerata: Quodlibet, 2008, pp. 54-57. [9] H. Lefebvre, Critica della vita quotidiana, II, Bari: Dedalo, 1977, p. 7. [10] Pentti Sammallahti, in Gérard Macé, "Une pensée en images", in Pentti Sammallahti, Parigi: Photo Poche/Actes Sud, 2007, p. 7. |

Marina Spunta e Jacopo Benci ringraziano Enrico Cocuccioni e David Forgacs.

Leicester - Roma, Aprile 2010